Bridging the Divide

The brouhaha over architect John Plumpton’s plan for the Toronto Islands has little to do with design.

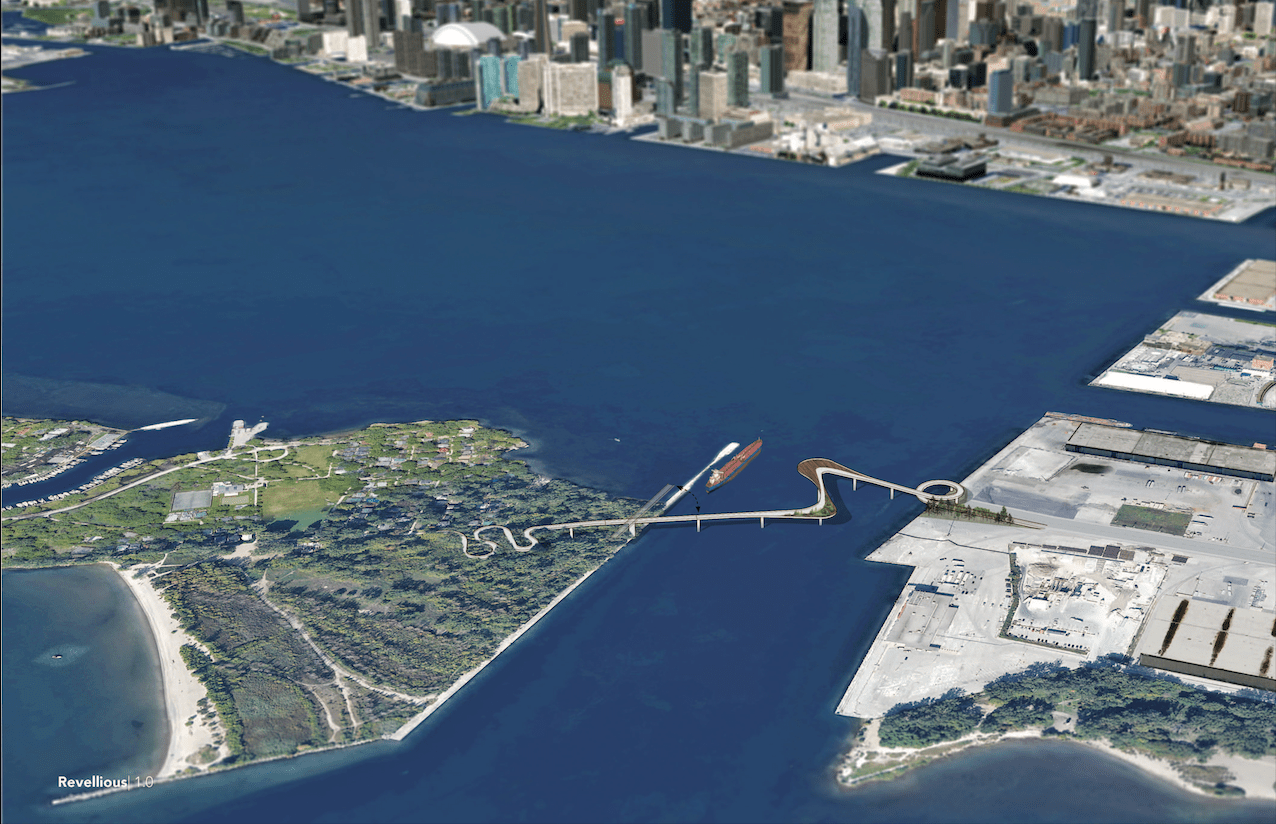

This fall, John Plumpton, principal of the Toronto firm RevelHouse, briefly became a lightning rod for controversy. At issue was his proposal for a pedestrian and cycling bridge that would cross the Eastern Channel, linking the mainland with the Toronto Islands currently accessible only by water taxi, kayak, and ferry—inefficient modes that limit foot traffic.

Plumpton’s span would pick up in the rapidly developing Port Lands district. It would then do a full loop to gain height, so that most sailboats might easily pass beneath it. At the centre of the channel, it would jog right and then left, creating hinge points that could double as parkettes. The final stretch would run low. This section would be “unfixed”: when large vessels approach, it would swing out, gate-like, allowing a clear passage.

Nobody would describe the plan as minimalist or utilitarian. “I come at everything from an experiential point of view,” says Plumpton, whose background is in theme park and entertainment design. Crossing the bridge, he adds, would be exhilarating and fun: “You’d have incredible views onto the skyline.”

The negative response has caught him off guard. All public-works projects should be subject to scrutiny, but the tenor of this debate—on social media and online message boards—has been surprisingly heated, as if Plumpton had proposed dynamiting the Scarborough Bluffs or paving over High Park. The critiques amount to three main points: that the bridge would be difficult or inconvenient to engineer, that it would be expensive, and that it would bring hordes of people onto the Islands, disrupting wildlife habitats and disturbing the peace.

In response to the engineering questions, Plumpton contends that the bridge is merely a provocation—the kind of thing architects sometimes cook up to spark debate—rather than a shovel-ready plan. He’s even working on a new drawing that would reroute the bridge to bypass residential areas and would switch the fixed and unfixed portions to better accommodate freighter traffic. Concerns about cost, he contends, are overstated too. At an estimated $150 million (perhaps more), the bridge would hardly be cheap, but poorer cities than Toronto have built more extravagant things without risking insolvency.

Then there’s the third argument—the one articulated forcefully by Island residents—that the bridge, and the many people who’d traverse it, would endanger the meadows, the dunes, and the habitats that support leopard frogs and migratory birds. Here, Plumpton suspects that there are more parochial concerns at play. Island dwellers, after all, have a vested interest in limiting foot traffic to their neighbourhood.

But do the rest of us? If City Hall decides to move forward with the project (the mayor hasn’t ruled it out), they should first subject it to rigorous environmental reviews and enforce bylaws to limit vandalism or habitat destruction. But if people are making conservation arguments to sustain a de facto moratorium not only on this bridge but on all prospective Island bridges, then they’re not arguing in good faith.

Ultimately, the controversy may be less about the merits of Plumpton’s design—as unorthodox as it might be—and more about access and affordability. Should the Islands be reachable mainly to people who purchase a ferry ticket and wait their turn in the queue? Or should we treat the region as a park like any other, available to anybody as part of Toronto’s collective patrimony? Plumpton is firmly in the latter camp. “We desperately need more downtown space,” he says. “Let’s give the harbour back to the public.”