A Ryerson Student Reimagines Abandoned Mines as Agricultural Hubs

Tatiana Estrina, a third-year architectural science student, won the ASCA’s 2018 Steel Design Student Competition for Uproot, a design that transforms open-pit mines into multi-tiered agricultural land

In Anthropocene, the Edward Burtynsky film that premiered at TIFF, the Toronto photographer meditates on the beauty – and environmental devastation – caused by industry, with his lens frequently landing on crater-like mines. But while his film focuses on the problems humanity has created, third-year Ryerson Architectural Science student Tatiana Estrina is focused on answers. And one such solution is Uproot: Once a Mine, Now a Garden, a concept that reimagines abandoned open-pit mines as fertile farmlands. No small feat.

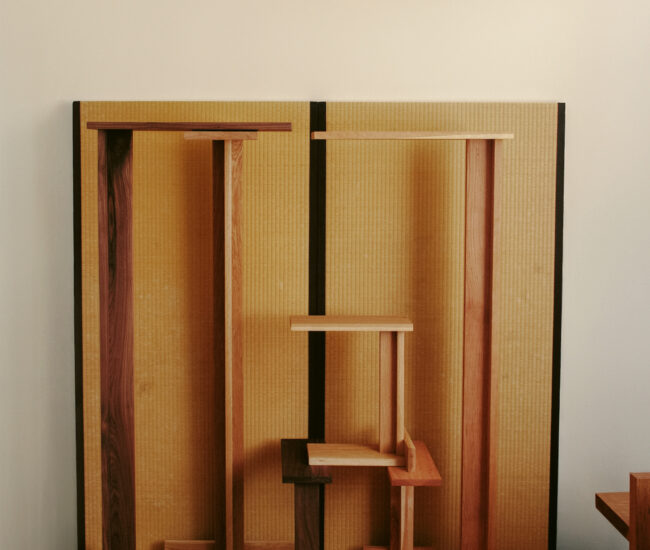

Estrina’s inventive intervention has already turned heads; it recently won first place in the 2018 Steel Design Student Competition, beating out 900 entries. Her design proposes a reservoir at the bottom of a mine, with an interior pod – featuring a central pump and piping system – rising skywards from water. The site features five stepped agricultural tiers, with irrigation emerging from Uproot’s tower, which serves as the site’s circulatory and social centre.

Each tier serves a different purpose: at its base, a pump extracts water from Uproot’s reservoir, which naturally collects water. The first level features a semi-enclosed seed storage area; the second storey features a pump, crop storage and a platform for gathering; the third tier features pipes that connect to walkways; the fourth level holds terraces, semi-closed areas and community space; the structure tops out with an entrance and welcome platform. It’s part St. Lawrence Farmers’ Market, part Mad Max oasis.

“Historically, people come together over food at the dinner table, but within this proposed design, the community bond is strengthened through activities related to the growth and production of sustainable food,” says Estrina. “Structural steel is strongest under tension, therefore steel was the natural material choice for a suspended structure like this.”

Indeed, community self-sufficiency is at the core of Uproot. And Estrina says she wanted to create an architectural solution to environmental, a next step for towns abandoned by industry. “I drew my inspiration from the belief that architecture is not simply for the privileged to enjoy or to be solely a display of material extravagance,” she says. “As Canada is still very much a resource economy, all Canadians are in some way connected to the fishing, forestry, and mining industries. However, as the resource economy evolves, various secondary and tertiary activities are developing as a result.”

Though Uproot can be implemented anywhere mining occurs, she says the design could be particularly useful in places like Timmins, where century-old mines have pocked the Ontario town with craters, particularly on Porcupine Lake. The concept aims to transform two things: a town’s post-industrial identity and its natural habitat. “In Ontario, there is a law requiring companies to re-vegetate the mining site itself, but they tend to plant very simple grasses and cease their involvement in the area after about five years,” she says. “Timmins itself is making an effort to reimagine a new community identity for itself that is separate from their main industry.”

Burtynsky, we imagine, would be proud.