Kapwani Kiwanga Underscores the Importance of Nature in New MOCA Exhibit

In her first major survey exhibition in Canada, the artist contemplates the varieties and mysteries of plant life

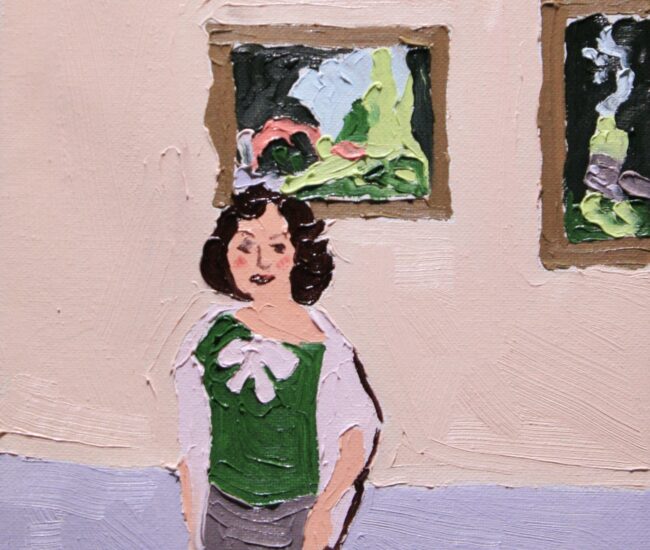

Enter the lobby of MOCA Toronto, and you’ll encounter a heavy curtain suspended from the ceiling, its material thick and woolly, like fibreglass insulation or bison pelt. This textile sculpture, called Elliptical Field (2023), is the work of Kapwani Kiwanga, the Hamilton-born, Paris-based artist. The piece is part of her current exhibit, Remediation, on show now through July 23.

Remediation occupies half of MOCA’s ground level and all of its second floor. Kiwanga made the piece in the lobby from sisal — a fibrous plant with spiky leaves and numerous industrial applications, including cordage and carpets. Originally cultivated by the Mayans and Aztecs, the species was later shipped to the Rift Valley, where it became a cash crop and then a chief export for the postcolonial United Republic of Tanzania, which used revenues from the sisal trade to support agrarian socialism.” Kiwanga describes the plant as “rough and soft and knotty,” as texturally rich as its complex history.

Hardy materials and fraught histories are Kiwanga’s speciality. Her exhibits usually focus on a central theme, which she researches exhaustively. One last year at New Museum, in Manhattan, dealt with the subject of illumination, with its links to surveillance and racism. (In eighteenth- century New York City, enslaved individuals were required under law to carry lanterns so that white citizens could monitor their activities.) The MOCA show, meanwhile, is all about plants — their mysteries, their medicinal effects, their status as crops, commodities, and curios. But a show about plants is also, inescapably, a show about humans.

The most politically urgent work in the gallery is Residue (2023), a wall tapestry of dried banana leaves, which Kiwanga describes as “witnesses of pesticidal overdose.” But she doesn’t limit herself to bleak subject matter. In Keyhole (2023), she reconstructs a keyhole garden, a type of circular, raised flowerbed. The plant species growing here all have restorative properties — elephant ear pulls formaldehyde from the air, broadleaf cattail removes industrial toxins from the water. For The Marias (2020), she commissioned an artisan to make paper reproductions of a Caesalpinia pulcherrima — a fronded plant, with elaborate stamens, which slaves from Suriname once used as an abortifacient, to resist bearing children into bondage. “Ongoing in my work,” says Kiwanga, “is the notion of plants as allies in various human endeavours.”

Once you become aware of this motif, you see it everywhere. The theme of nostalgia, however — a common one in art about nature — is conspicuously absent. There’s no pining for a preindustrial Eden. “I don’t believe in a pristine, untouched, pre-contact place,” says Kiwanga. Like vines encircling a trellis, plant life is intertwined with human industry. We can’t undo this relationship. The goal, for Kiwanga, is to harmonize it, ensuring we give as much as we take.

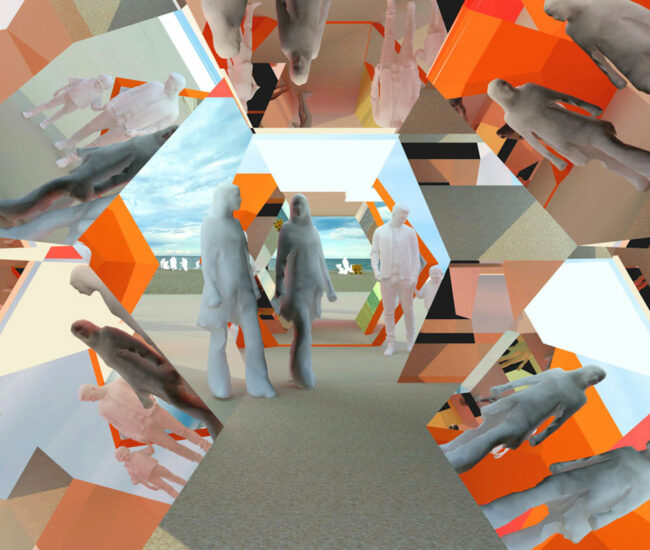

The most idiosyncratic work in Remediation is a suite of three PVC sculptures inspired by old Wardian cases — sealed terrariums that enabled tropical plants to grow in Victorian London despite the filthy air. Rather than imitate these typologies, Kiwanga has abstracted them, creating biomorphic forms that bulge and taper. She has also inverted their purposes, imagining these sculptures as prototypes for future horticultural technologies: not display cases, but armatures, around which plants can grow. “The plants would enclose the structures,” she says, “melding with them and resisting capture.”