The Making of Modern Toronto

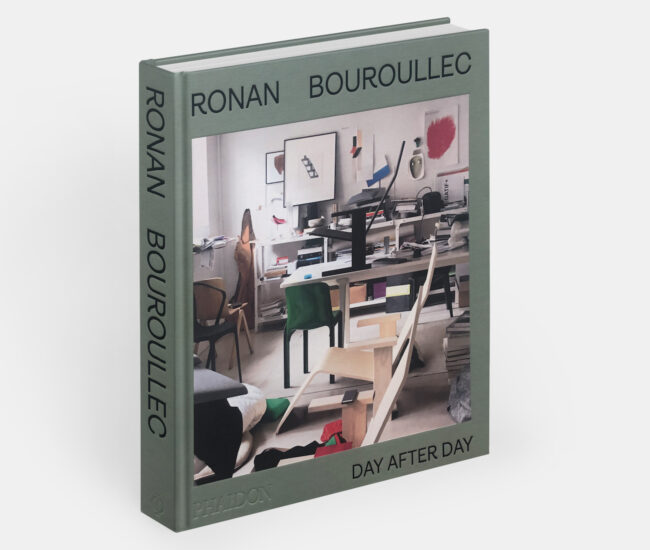

The work of Jerome Markson, a Toronto-born architect, is the subject of an essential new book by Laura J. Miller

Flip though the opening pages, and the architecture of Jerome Markson is hardly perceptible. Instead, Laura J. Miller’s newly published Toronto’s Inclusive Modernity: The Architecture of Jerome Markson begins with 14 consecutive pages featuring hundreds of photographs stitched together to create a jagged tapestry of the city. Only halfway through do we get our first glimpse of a Markson complex, as the Alexandra Park Public Housing Estate joins an eclectic downtown milieu. Here is architecture that emerges from – and weaves together – the urban fabric.

Presented this way, Scott Norsworthy’s contemporary photographs of Markson’s projects focus less on buildings than on the rhythms of daily life playing out in and around them. The same was true for Markson’s own use of photography. We are introduced to the True Davidson Acres Metro Home for the Aged, for example, by two intimate portraits of residents, and to a Martin Grove housing complex by a shot of children playing around a makeshift outdoor pool. So what does any of this tell us about architecture?

Plenty. For the 90-year-old Markson, an uncommon sensitivity to urban – and individual – context is expressed in photography. While the book’s stitched collages situate Markson’s work within Toronto’s contemporary fabric, the architect’s own photographic commissions favoured lived experience over architectural spectacle. As Miller puts it, many of the archival images unfold with “the architecture as backdrop rather than subject.”

But there’s lots of architecture too. Over the course of a nearly six-decade career, Markson’s work transformed a transforming city. While luxurious private homes and marquee apartment buildings – including downtown’s playfully Haussmannian Market Square Condominiums – dot the portfolio, Markson’s architectural vision is perhaps most vividly manifested through his extensive work in non-profit housing.

East of the St. Lawrence Market, the David B. Archer Co-operative Housing development is a case in point. Completed in 1979, the red-brick complex introduces townhouses and a modest apartment building around a new internal street to create what Miller describes as a sense of “animated domesticity:” entryways, stoops, windows and balconies are visually emphasized to underline the presence of each individual home. For a dense community built from scratch on formerly industrial land, a surprisingly intimate atmosphere pervades, with residential interiors elegantly contoured to overlook the playground and internal street. “The place feels friendly,” writes Alex Bozikovic.

The Pembroke Mews housing complex on Sherbourne Street is another example of Markson’s forward-thinking 1970s design. Built for the City of Toronto’s non-profit housing agency, the carefully scaled infill project contributed to ongoing urban densification while deftly avoiding the demolition of neighbouring 19th-century housing stock. Topped by a two-tier bridge and flanked by an arched stair tower, the pedestrian passage that runs through the heart of the site brings a quiet sense of whimsy – and of place – to the community.

And then there’s Alexandra Park. Across an 18-acre site, the mid-1960s design – developed by Markson with Klein and Sears and Webb Zerafa Menkès – introduced an almost unprecedented range of typologies and unit types to a public housing complex. Here, too, careful attention was paid to the relationship between public and private space, with the bay and clerestory windows of brick townhouses lining a varied pedestrian landscape that forms the community’s inner circulation. Larger apartment buildings (and a seniors’ residence) line the site’s perimeter to serve as ingresses to the community. But not for long.

Markson’s work was not immune to its era’s characteristic urban planning mistakes. Today, most of Alexandra Park is slated to be mostly demolished and redeveloped with mixed-use density. Despite its architectural qualities, the community – which was never adequately maintained by the city – is a meandering mid-century “super-block” that lacks through streets and feels cut off from its surroundings. While Markson and his design partners pushed to maintain the pre-existing street grid and to implement a radically progressive “repair and replace” model that would have integrated 19th-century housing stock into the scheme, the eventual reality differed significantly from this vision.

Still, Markson’s body of work shaped the city for the better. Assessing the Queen West Community Health Centre (completed in 1997), Christopher Hume wrote that “Markson’s quiet mastery makes him one of the rare architects who creates cities while designing buildings.” For all its faults, even Alexandra Park is itself a testament to a spirit of inclusivity.

As Miller notes, the social housing project was highlighted in a 1969 issue of The Canadian Architect, where the complex was introduced by a two-page spread depicting a trio of children at play. “All three are laughing. One child is black, the other two, white,” Miller writes. “If there is architecture to be seen at all in this image, it is in the stark abstractions of the children’s shadows on the bright pavement, their pattern dazzling against a dark backdrop.”

“I could not help but recognize that in 1969 such an image would have been, to some in the United States and other places, quite incendiary,” Miller notes. Yet there it was. Markson’s use of architectural photography reveals buildings not as objects or sculptures but as conduits through which life unfolds.

Indeed, according to Miller, the best of Markson’s work offers “in the apparent form of a space an underlying, mutable identity.” While Markson’s buildings are expressive, subtly playful and often surprising, they are not characterized by any singular style or aesthetic signature. “From the outset, Markson’s architectural work was not easily pigeonholed,” writes Miller.

If Markson isn’t quite as well-known as his foremost Toronto contemporaries (like Jack Diamond or Eberhard Zeidler) this deferential sensibility is part of the reason why. But as Miller’s book makes clear, his distinctive ethos fostered a legacy of built work that – at its best – epitomizes the aspirational inclusivity and openness of a city now touted as the most diverse in the world.

There are important lessons in this. At the outset of Markson’s career, Toronto was North America’s fastest-growing city – just as it is today. In the context of this explosive growth, Markson’s portfolio is a testament to both humility and humanity. The attention to context and community in the architect’s many public housing and co-operative commissions is astonishing, especially when one considers the absence of such qualities in the great number of condominiums now sprouting up across the city – let alone the few non-profit housing projects currently being built. We ought to follow Markson’s example in how to build non-market housing. And we ought to build a hell of a lot more of it.

Born and educated in Canada’s biggest metropolis, Markson is a distinctly Toronto architect. Today, his buildings form part of the background of daily life. Perusing the book, I came across my own elementary school – a Markson building, not that I ever realized it. But even if we don’t always recognize Markson’s buildings as his, they offer a vital “setting for human interaction and the appearance of the individual,” Miller writes. And somewhere between and beyond those children at play, the seniors in quiet repose, and the thousands of people moving through their everyday lives, they are the setting for Toronto as we know it.