The World and Everything in It

A new survey exhibition by the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans is a feast for the eyes – and a punch to the gut

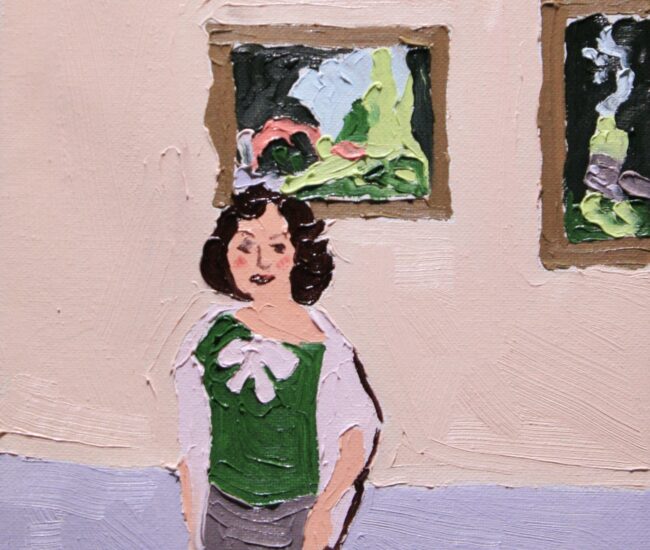

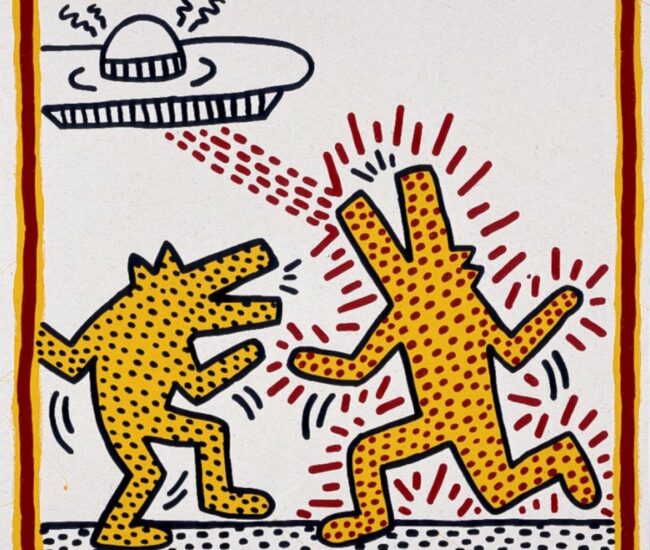

Here’s a partial list of things that Wolfgang Tillmans, the world’s greatest photographer under 60, has depicted in art: textiles, flesh, genitalia, misshapen vegetables, snow, TV static, transit systems, the transit of Venus, the ocean, Frank Ocean, clothed people, naked people, people dancing, kissing, hanging out in trees. Tillmans rose to fame in the ’90s as a chronicler of the gay club scene in London and his native Berlin, but he has since wandered, camera in hand, in countless new directions.

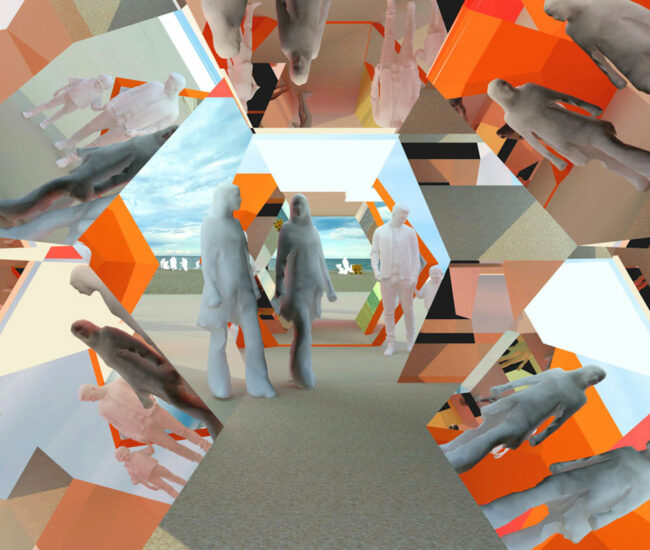

To look without fear, a MoMA survey exhibition now at the AGO, features more than 350 prints – most of them frameless and stuck to the wall with simple adhesives – yet it cannot possibly capture the range of Tillmans’s interests.

I met the artist in April with the intention of asking about my favourite piece: Concorde Grid (1997), a series of 56 photographs of the legendary supersonic aircraft in flight. In London, Tillmans would wait patiently under its flight path for his droop-nosed subject to appear. “I was intrigued by the democratic quality of Concorde,” he says. “Everybody who saw it felt something special.” Boarding passes were for the rich. But to spot the aircraft and experience a sense of late-space-age wonder? We could all, at least, have that.

Unsurprisingly, the photographs in Concorde Grid consist mostly of sky – washes of hazy or crepuscular colour. “The project primed me,” Tillmans says, “for works I did years later of pure colour.” Those prints, produced by exposing photographic paper to light, can be read as companion pieces to the Concorde series. Then again, in a Tillmans exhibition, pretty much everything could be a companion piece to everything else.

It’s up to you to map out the relationships. If you visit the show, take a moment to appreciate Window Caravaggio (1997): five postcards and a single lily arranged on a ledge at Tillmans’s London flat. Then look closely at a nearby portrait of Kate Moss and see if you can spot the shadow of that same window on the fabric backdrop. I wouldn’t have noticed this connection had Tillmans not pointed it out to me, but once I started searching for visual rhymes, I found them everywhere. In my mind, images of ocean surf melded with those of rippling muscles or rumpled laundry. The head of broccoli that Moss holds up evoked, for me, the moonscapes and – for lack of a better word – testicle-scapes that appear in the show.

The exhibition is lively and fun, and yet, when it first opened at MoMA, it made some critics profoundly sad. Surely, these feelings were rooted in awareness of passing time: the young people in Tillmans’s early shots are no longer young, and some are no longer living. The most poignant images depict the painter Jochen Klein, Tillmans’s lover and muse, who died of AIDS-related illnesses in 1997. The Europe of Tillmans’s youth is changing too, as the dream of a united continent curdles into a paranoid nightmare, and as a culture of pulsing nightclubs and sweaty loft parties gives way to a new era of smartphones, doom-scrolling and endemic loneliness.

Tillmans isn’t nostalgic. The ’90s, he points out, was a scary decade in which to be young and gay. “I felt the tragedy and heaviness of the era very much,” he says. And yet, his early photographs – documents of that brief window of time between the Maastricht Treaty and the arrival of social media, when house music was ascendant and ecstasy came in a pill – seem to portend a better future. They suggest that a new culture of liberty and conviviality might finally be dawning. Does anybody feel this way today?

In 2000, a Concorde took off from Charles de Gaulle Airport and crashed into a hotel. What’s left of the dream can be seen at the AGO, in 56 photographs taped to the gallery wall. AGO.CA.